On September 11, 1857, Mormon settlers in Southwest Utah massacred 121 men, women and children on a wagon train bound for California. The wagon train was made up of families from Benton, Carroll, Johnson, and Marion Counties of Arkansas. Prior to the Oklahoma City bombing, the Mountain Meadows Massacre was the largest act of terrorism ever heaped on civilians by other Americans.

The wagon train selected two leaders for the trip: Captain Alexander Fancher of Benton County assumed leadership of the wagons and people; and Captain John Twitty Baker was the herd boss of a thousand cattle and the drovers. Both men had made prior trips to California and were highly seasoned leaders.

The wagon train became known in history as the Fancher-Baker train in their honor.

Click the Tabs on the Left to Learn About the History of the Mountain Meadows Massacre

The wagon train was made up of several large family groups. Prominent among those large family groups were the Bakers, Camerons, Dunlaps, Fanchers, Huffs, Jones, Millers, Mitchells, and Tackitts. The Baker, Dunlap, and Mitchell wagons originated in Carroll and Marion Counties of Arkansas while the Cameron, Jones, Miller and Tackitt families hailed from Johnson County. Captain Alexander Fancher and Peter Huff lived in Benton County near Gentry before starting on the trip. All were recognized as good, hard-working people.

Several single men were working their way to California. Among them were the surnames Basham, Beach, Beller, DeShazo, Edwards, Farmer, Hamilton, Hayden, Hudson, Poteet, Prewit, Reed, Smith, Stallcup, Stevensen, Wilson, and Wood. The single men were from the same general areas as the families with wagons except some may have been from Newton County.

The Fancher-Baker wagon train was one of the most wealthy to travel across the West. Over 25 families were represented in that party of emigrants. The group had some 30 wagons loaded with their best furniture, clothing and food items. Most people walked to make the loads lighter for the oxen or mules to pull. Four carriages were available for carrying women, small children and sick folks. A cattle herd of 900-1,000 head traveled some distance from the wagons.

There were 200 horses including a famous racing mare named One-Eyed Blaze. A prize stallion was valued at $2,000. Most of the families had gold for buying ranches once they reached California. Some concealed their gold in the wagon bolsters to avoid being robbed along the way.

Historians estimate that the wagon train was worth $70,000 to $100,000 in 1857. In today’s money, their worth would be well over a million dollars.

Although the early 1850s was a prosperous time in Arkansas, the Panic of 1857 brought hardships to many Ozark families. They thought California offered them a better future for their growing families. Others were looking for the adventure of moving west. Many of the single men were working their way to California by eating the dust of a cattle drive. The young men called it “seeing the elephant.”

Captains Fancher and Baker were making the trip to make money. Their cows cost $10 in Arkansas and sold to the beef-hungry gold miners in California for $100. Captain John Twitty Baker planned to return to Arkansas after selling his cows. Captain Fancher brought his entire family with plans to establish a permanent home in California.

The destination of the Fancher-Baker wagon train was Tulare County, California. Captain Fancher’s brother owned a ranch in that area of California. In fact, John Fancher registered the first cattle brand in Tulare County in 1852. Other Arkansas people such as Basil Parker of Newton County were settling in Tulare County. That part of California was an ideal location for growing livestock. It offered good winter grazing at lower elevations and summer grazing among the giant trees of the Sierra Mountains.

In 1849, Lewis Evans of Fayetteville and 75 Cherokee Indians from Tahlequah, Oklahoma made a new trail from Arkansas to California. It was known as the Cherokee Trail. The Fancher-Baker wagon train followed the Evans route to Ft. Bridger, Wyoming. They traveled across Benton County to the Grand Saline crossing (Salina, Oklahoma today) of the Grand River. Here the families from Johnson County joined those from Carroll, Marion and Benton Counties. After crossing Grand River the wagon train proceeded to the Verdigris River which they crossed at Coody’s Bluff. From there they followed the Arkansas River to join the Santa Fe Road at McPherson, Kansas. The Santa Fe Road followed the Arkansas River to Bent’s Fort in Colorado. Here the wagon train turned north to Wyoming. The Cherokee Trail crossed Southern Wyoming to Ft. Bridger where it joined the main California Trail.

Most wagon trains passed through Salt Lake City. They were usually able to buy foodstuff to re-supply their wagons. While camped near Salt Lake City, local Mormons advised the Fancher-Baker wagon train to take the South California Road and the Old Spanish Trail from Salt Lake City to California. During the month of August the wagon train moved to their final campsite at Mountain Meadows in Southwest Utah.

The days on the trail were long, dusty and tiring. Many folks became cranky and mean tempered. Captain Fancher loved music and dancing. When he saw his people becoming bored or cantankerous, he pulled out his fiddle and a dance began. Soon the folks were in a good mood for further travel.

Oxen sometimes escaped during the night and tried to return to their Arkansas homes. Sometimes it took several days to catch up with them and bring them back to the wagon train. Cattle often tried to follow migrating buffalo herds. The drovers had to chase them down and return them to the herd. There was very little sickness during their trip west.

Peter Huff was the only wagon train death before reaching Mountain Meadows. He died from a spider bite and was buried beside the trail near Ft. Bridger, Wyoming.

Mormon settlers lived in several states before moving to Utah in 1847. After being driven out of Missouri, the LDS Church settled in Nauvoo, Illinois. Their leaders were thrown in jail. A mob attacked the jail and killed their Prophet Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum. Joseph Smith’s followers felt mistreated in Missouri and Illinois. They wanted to move to an isolated place where they could be left alone. Brigham Young assumed leadership of the Mormons and moved them to Utah. Utah was unsettled when the Mormons arrived there.

On July 24, 1857 Brigham Young and his followers held a picnic up Cottonwood Canyon near Salt Lake City. They were celebrating their 10th anniversary in Utah. During that picnic, Brigham Young received word that the United States Army was moving toward Utah; he was to be replaced as governor of Utah Territory. Brigham Young became angry and made a fiery speech to his followers. He advised them not to sell supplies to wagon trains and prepare to fight the U.S. Army. The picnic occurred one week before the Fancher-Baker wagon train reached Salt Lake City.

Some historians cite robbery as a motive for attacking the wagon train. Others believe that the Mormons were avenging the death of Prophet Joseph Smith and Apostle Parley Pratt. They were angry because Parley Pratt had been murdered at Alma, Arkansas a short time before the wagon train reached Utah. While the wagon train moved through Utah, Jacob Hamblin brought 12 Indian chiefs to Salt Lake to see Brigham Young. He gave the Indians permission to attack wagon trains crossing the Territory. Brigham Young prepared to fight the United States Army. To prepare his followers for the coming fight Brigham Young sent George A. Smith, his second in command, to Southern Utah to preach inflammatory sermons.

As the wagon train moved south through Utah, a plot to rob and kill the group was being set in place. Colonel William Dame was the military leader in the region. His orders were to “decoy and exterminate” the wagon train. Those orders were received in Cedar City by Mormon military and church leaders John D. Lee, Philip Klingensmith, John Higbee, and Isaac Haight. The Cedar City leaders planned the final episode to appear as an Indian massacre. Indian Agent John D. Lee assumed the responsibility for involving local Paiute Indians in the massacre. The emigrants were able to buy some grain at Corn Creek where Dr. Garland Hurt, a non-Mormon Indian agent, was teaching the Indians to farm.

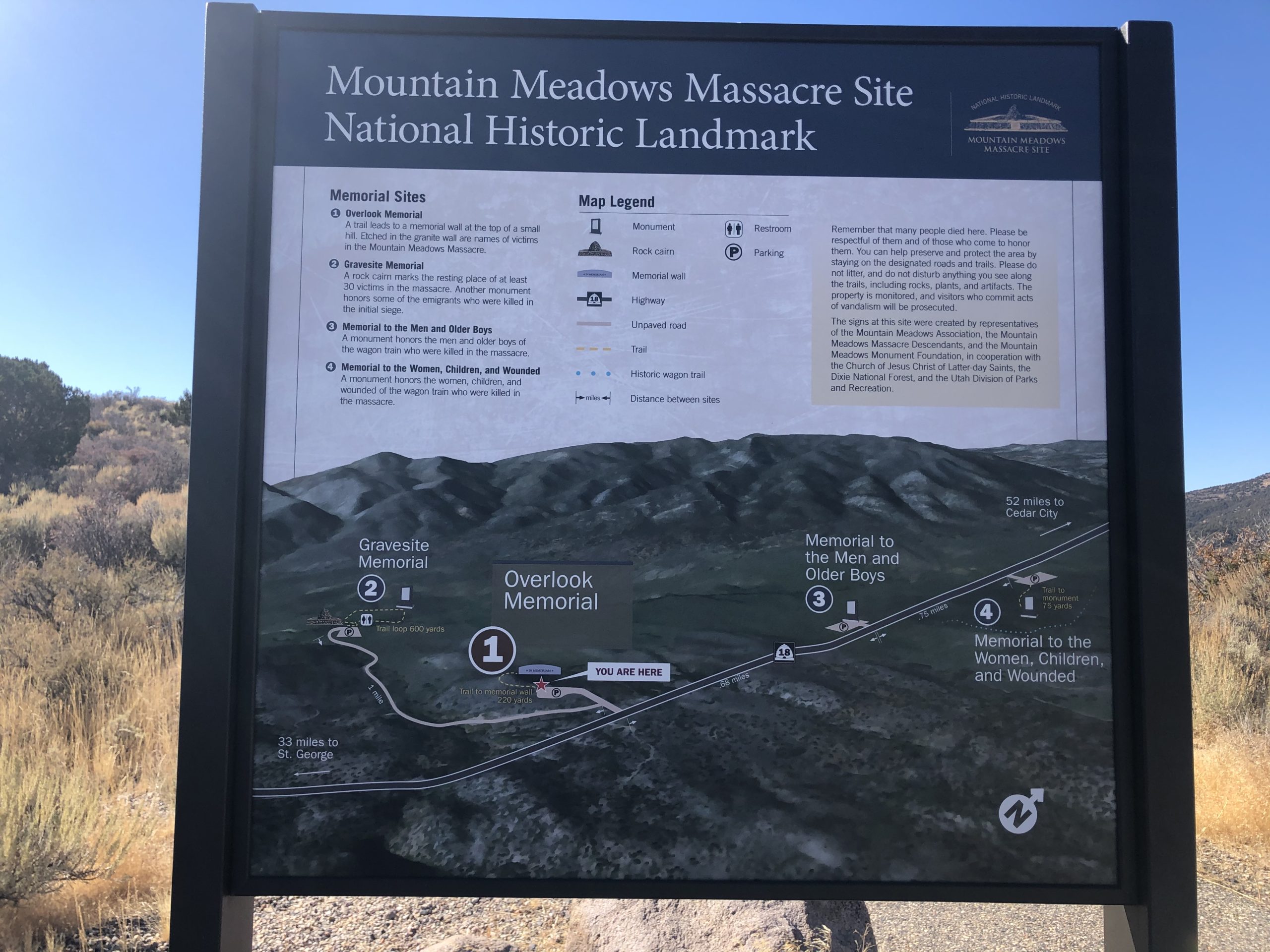

Their final campsite at Mountain Meadows was on a small mesa a few hundred feet from a large spring. The emigrants settled into their camp on Friday with plans to spend several days. They were planning a desert crossing and wished their animals to be well-fed on the lush meadow grass. The women washed clothes and the children romped through the sagebrush.

On Monday morning the emigrants were having breakfast of quail and cottontail rabbit. Suddenly gunfire rained down on them from the nearby ravine and hillsides. John D. Lee and a group of Mormons were painted up as Indians. Some Paiutes were involved in the first assault on the wagon trains. The first volley killed seven people and wounded several others. Quickly the emigrants pulled their wagons into a circle. Holes were dug for the wagon wheels to drop the wagon beds on the ground. Dirt was thrown against the wagon beds to keep bullets from coming under the wagons.

The emigrants returned fire and hit two Indians. During the next three days, the Mormons kept the group under siege. They shot at the emigrants when they attempted to get water from the spring. The Paiutes threatened to quit the siege but were talked into staying around by John D. Lee.

On Wednesday night, William Aiden offered to ride out for help. When he stopped to water his horse at Leachy Spring, he was met by William Stewart and his companions. As he started to leave he was shot from the saddle. Captain Fancher asked the three wagon train scouts to attempt an escape on Thursday evening. He asked them to go to California and tell “Masons, Methodists, and Free Men Everywhere” what happened to the wagon train. They were followed for ninety miles and killed by a Mormon group led by Ira Hatch.

By Friday the children and wounded were suffering from thirst. Their ammunition was running low. The emigrants were in a desperate situation. John D. Lee rode into camp under a white flag. He told the emigrants that the Indians had agreed to let the Mormon Militia escort them to Cedar City. A desperate wagon train agreed to the plan. They were asked to give up their guns to show good faith to the Indians. The guns were loaded into a wagon and driven away. Wounded and small children were loaded into two wagons and sent toward Cedar City. Women and girls followed the wagons which were hauling their babies. After the women passed around Massacre Hill and turned north on the California Road, each emigrant man was paired up with a member of the Iron County Militia. The men and their guards started along the same route as their women and children.

Suddenly, John Higbee gave the command “Alright men, do your duty.” Each Mormon turned and killed the emigrant by his side. John D. Lee was beside the wagonload of wounded. He repeated Higbee’s command and started killing the wounded, women and children. Within a few minutes 121 men, women and children were killed by fellow white men. Recent forensic evidence shows that Indians had very little involvement in the final massacre. After the killing stopped, seventeen sobbing children were hauled to Hamblin’s ranch and parceled out to many of the same people whom they observed killing their parents.

The Indians got very little from the wagon train property. Some canvas wagon covers and grain supposedly went to the Indians. They ate a few head of cattle during the week of siege.

Many of the cows were branded with the church brand. Sixty to seventy head were traded to Mr. Hooper of Salt Lake City for shoes. Clothes and jewelry were stripped from the dead by the people who committed the massacre.

The clothes were stored in the church commissary in Cedar City. Some clothing was doled out to Indians and billed to U.S. Government Indian funds. Some gold from the wagon train entered the LDS Church treasury.

Wagons, horses, carriages, and furniture were distributed among the Mormon families of Southern Utah.

Most historians agree that 121 men, women and children were killed in the week-long siege and final massacre. Ninety of those killed were under 20 years of age. Although the Mormons attempted to spare children under eight years of age, some very small children were shot by accident. Mormons believed that children under eight were “innocent blood” and should not be killed. The victims were stripped of clothing and left unburied for the next 18 months. Other wagon trains passed through Mountain Meadows after the massacre. They reported that wolves were dragging the exposed bodies about the Meadows.

In May of 1859, Brevet Major James H. Carleton came to Utah from Ft. memorial Tejon, California. He was bringing the payroll to soldiers at Camp Floyd, Utah. Captain Reben Campbell and his soldiers came from Camp Floyd to meet Major Carleton at Mountain Meadows. They collected the remains of the massacre victims and buried them in several mass graves. Major Carleton buried 34 bodies in a mass grave near the spring where the emigrants had camped. He had his soldiers erect a 24 foot cross over the graves. Upon the cross the soldiers carved the words “Vengeance is Mine Saith the Lord, I Will Repay.” They also carved a large rock with “Here 120 men, women, and children were murdered in Cold Blood in early September 1857. They were from Arkansas.” The Carleton memorial to the massacre survivors was destroyed by Brigham Young and his followers in 1861.

Seventeen small children survived the massacre. All were under seven years of age. After the massacre, the children were hauled about four miles to Jacob Hamblin’s ranch.

Here they were divided up among Mormon families in the Cedar City area. Their names were changed to hide their identity to the outside world. One year-old Sarah Dunlap had an arm almost severed by a Mormon musket ball.

Two of Sarah’s older sisters also survived the massacre. They begged to stay with their wounded little sister. Rachel Hamblin’s mothering instinct overcame her and she agreed to take all three of the Dunlap sisters.

Sally Mitchell had a bullet-nicked ear from the same shot that killed her father.

Eighteen months after the massacre Dr. Jacob Forney and Captain James Lynch came to the area and searched for the children. The Mormons claimed the Indians had the children. The children claimed they were never kept by the Indians. After an intense search, the seventeen little orphans were taken into the custody of Dr. Forney.

According to Dr. Forney, the children were infested with lice and poorly clothed. Dr. Forney took the children to Santa Clara and hired women to make clothes for them.

The survivors were then taken to Salt Lake City. From there, they were returned to Arkansas. Their relatives met them at Carrollton, Arkansas on September 25, 1859 and took them into their homes.

The massacre was carried out by John D. Lee and 54 members of the Iron County Militia. Judge Cradlebaugh came to Cedar City in 1859 and tried to bring the guilty to justice. Arrest warrants were sworn out for over a hundred people, including Brigham Young. His military escort was pulled from him, leaving it unsafe for him to continue his investigation. For his own personal safety, Judge Cradlebaugh returned to Camp Floyd with the soldiers.

Very little was done to bring the murderers to justice until after the Civil War. Writers such as Mark Twain called for justice. Newspapers started asking questions about the massacre. To satisfy that renewed call for justice, John D. Lee was brought to trial in 1875. A mixed jury of Mormons and Gentiles did not convict Lee. He was brought to trial a second time with an all-Mormon jury. Lee was sentenced to death. In May 1877, twenty years after the massacre, John D. Lee was taken to Mountain Meadows and executed by firing squad. He was the only one to be brought to justice for the massacre. Fifty to sixty others were guilty of murder but walked free. A few were kicked out of the LDS Church for a short time. Others went into hiding in Arizona and Mexico to avoid being arrested. Most of them continued to enjoy the perks and privileges of the LDS Church and live comfortable lives in Utah.